i gut to be on the 5:48 am bus, so with my pallgies, i aint gut time to blog.

heres a pitcher of a friendly dog that visited us yesterdy:

‘I had reasoned this out in my mind, there was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other.’

It was a new and special revelation, dispelling a painful mystery, against which my youthful understanding had struggled, and struggled in vain, to wit: the white man's power to perpetuate the enslavement of the black man. "Very well," thought I; "knowledge unfits a child to be a slave." I instinctively assented to the proposition; and from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom.

‘What was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do to me was kill me and it seemed like they'd been trying to do that a little bit at a time ever since I could remember.’

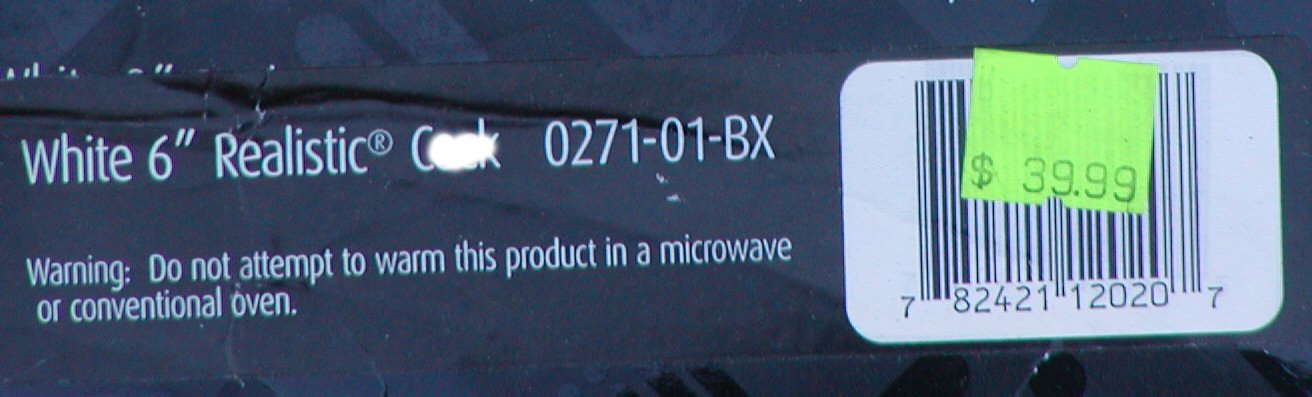

I believe America must pursue the tremendous possibilities of science, and I believe we can do so while still fostering and encouraging respect for human life in all its stages. (Applause.) In the complex debate over embryonic stem cell research, we must remember that real human lives are involved --both the lives of those with diseases that might find cures from this research, and the lives of the embryos that will be destroyed in the process. The children here today are reminders that every human life is a precious gift of matchless value. (Applause.)heres sum pitchers ye probly aint seen n mayhap ye dont wonta see em. i warn ye in add vants bout how thar sum verr ugly sites ifn ye foller them lanks. so ye mite wonta perteck yerself by gittin ye sum argon down in the pit cnn or fox news or msnbc or inny of them netwurk news cumpnys or even the new york times or the washington post or inny other majur amurkin newspaper.

The Bush administration's first response was equally straightforward. The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Richard B. Myers, told reporters last week that the U.S. commander in Afghanistan believed the violence "was not at all tied to the article in the magazine." Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice pledged that "appropriate action" would be taken if the allegations proved true. But then the administration's spinners, led by Pentagon and White House spokesmen, took over. The result has been a cynical campaign to capitalize politically while deflecting attention from serious issues.

[emphasis by buddy don]

Accounts of abuses at the actual American detention center at Guantánamo Bay, including Newsweek magazine's now-retracted article on the desecration of the Koran, ricochet around the world, instilling ideas about American power and justice, and sowing distrust of the United States. Even more than the written accounts are the images that flash on television screens throughout the Muslim world: caged men, in orange prison jumpsuits, on their knees. On Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya, two satellite networks, images of the prisoners appear in station promos.

For many Muslims, Guantánamo stands as a confirmation of the low regard in which they believe the United States holds them. For many non-Muslims, regardless of their feelings toward the United States, it has emerged as a symbol of American hypocrisy.

"The cages, the orange suits, the shackles - it's as if they're dealing with something that's like a germ they don't want to touch," said Daoud Kuttab, director of the Institute of Modern Media at Al Quds University in Ramallah, in the West Bank. "That's the nastiness of it."

The Bush administration's response to the Newsweek article - a general condemnation of prison abuses, coupled with an attack on the magazine - apparently did little to allay the concerns of many Muslims. Then on Thursday, the International Committee of the Red Cross issued a report detailing the many complaints from detainees at Guantánamo about desecrations of the Koran between early 2002 and mid-2003.

In India, a secular country by law whose people and government are growing increasingly close to the United States, a cartoon appeared in Midday, an afternoon tabloid, on Friday showing a panic-stricken Uncle Sam flushing copies of Newsweek magazine down a toilet.

To the cartoonist, Hemant Morparia, it appeared as though the Bush administration's answer to the problem was to bury the truth.

habits: easy to make, hard to brake; goodns make ye, badns brake ye.since my habit of takin a look at the new york times ever mornin aint broke, i ended up readin the mane articull on the frunt page, witch it made me so mad i wonted to cry.

Even as the young Afghan man was dying before them, his American jailers continued to torment him.i reckun ye kin see that this aint the kinda thang ye wonta thank our folks is a'doon over thar, so dont read that thar articull, speshly not to the end.

The prisoner, a slight, 22-year-old taxi driver known only as Dilawar, was hauled from his cell at the detention center in Bagram, Afghanistan, at around 2 a.m. to answer questions about a rocket attack on an American base. When he arrived in the interrogation room, an interpreter who was present said, his legs were bouncing uncontrollably in the plastic chair and his hands were numb. He had been chained by the wrists to the top of his cell for much of the previous four days.

Mr. Dilawar asked for a drink of water, and one of the two interrogators, Specialist Joshua R. Claus, 21, picked up a large plastic bottle. But first he punched a hole in the bottom, the interpreter said, so as the prisoner fumbled weakly with the cap, the water poured out over his orange prison scrubs. The soldier then grabbed the bottle back and began squirting the water forcefully into Mr. Dilawar's face.

"Come on, drink!" the interpreter said Specialist Claus had shouted, as the prisoner gagged on the spray. "Drink!"

At the interrogators' behest, a guard tried to force the young man to his knees. But his legs, which had been pummeled by guards for several days, could no longer bend. An interrogator told Mr. Dilawar that he could see a doctor after they finished with him. When he was finally sent back to his cell, though, the guards were instructed only to chain the prisoner back to the ceiling.

"Leave him up," one of the guards quoted Specialist Claus as saying.

Several hours passed before an emergency room doctor finally saw Mr. Dilawar. By then he was dead, his body beginning to stiffen. It would be many months before Army investigators learned a final horrific detail: Most of the interrogators had believed Mr. Dilawar was an innocent man who simply drove his taxi past the American base at the wrong time.

The story of Mr. Dilawar's brutal death at the Bagram Collection Point - and that of another detainee, Habibullah, who died there six days earlier in December 2002 - emerge from a nearly 2,000-page confidential file of the Army's criminal investigation into the case, a copy of which was obtained by The New York Times.

In February, an American military official disclosed that the Afghan guerrilla commander whose men had arrested Mr. Dilawar and his passengers had himself been detained. The commander, Jan Baz Khan, was suspected of attacking Camp Salerno himself and then turning over innocent "suspects" to the Americans in a ploy to win their trust, the military official said.have ye gut the point? ye dont wonta read that thar articull, do ye? ye wonta sleep peaceful, thankin how we mus be on gods side, how thonly reason muslims mite be upset with amurka is how newsweek dint git its story strate. tiz easier to bleev that than to read bout this awful stuff bein reported bout us.

The three passengers in Mr. Dilawar's taxi were sent home from Guantánamo in March 2004, 15 months after their capture, with letters saying they posed "no threat" to American forces.

They were later visited by Mr. Dilawar's parents, who begged them to explain what had happened to their son. But the men said they could not bring themselves to recount the details.

"I told them he had a bed," said Mr. Parkhudin. "I said the Americans were very nice because he had a heart problem."

In late August of last year, shortly before the Army completed its inquiry into the deaths, Sergeant Yonushonis, who was stationed in Germany, went at his own initiative to see an agent of the Criminal Investigation Command. Until then, he had never been interviewed.

"I expected to be contacted at some point by investigators in this case," he said. "I was living a few doors down from the interrogation room, and I had been one of the last to see this detainee alive."

Sergeant Yonushonis described what he had witnessed of the detainee's last interrogation. "I remember being so mad that I had trouble speaking," he said.

He also added a detail that had been overlooked in the investigative file. By the time Mr. Dilawar was taken into his final interrogations, he said, "most of us were convinced that the detainee was innocent."

The Puritans were a group of people who grew discontent in the Church of England and worked towards religious, moral and societal reforms. The writings and ideas of John Calvin, a leader in the Reformation, gave rise to Protestantism and were pivotal to the Christian revolt. They contended that The Church of England had become a product of political struggles and man-made doctrines. The Puritans were one branch of dissenters who decided that the Church of England was beyond reform. Escaping persecution from church leadership and the King, they came to America.

The concept of religious persecution was not a new one to England, Queen Elizabeth reestablished the Protestant religion in England. In 1559, Cranmer's [revised] Book of Common Prayer became the law of English liturgy. The mass was outlawed, and Englishmen were compelled to attend the Anglican Church or pay a shilling. Catholics were forbidden to even hold Catholic literature. The government ordered the destruction of religious images in churches. In 1581, Parliament passed a law that conversion to Catholicism would be punished as high treason. Over 100 priests and 60 laymen were executed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

English persecution under the reign of Elizabeth, however, did not confine itself solely to the Catholics. The Puritans also felt the heavy hand of the state. John Whitgift, her minister in the Canterbury see, subjected Puritan preachers who refused to support the state religion to such intense religious inquiry that it was compared to the worst stories told about the Spanish Inquisition.

The Society of Friends may be traced to the many Protestant bodies that appeared in Europe during the Reformation. These groups, stressing an individual approach to religion, strict discipline, and the rejection of an authoritarian church, formed one expression of the religious temper of 17th-century England. Many doctrines of the Society of Friends were taken from those of earlier religious groups, particularly those of the Anabaptists and Independents, who believed in lay leadership, independent congregations, and complete separation of church and state. The society, however, unlike many of its predecessors, did not begin as a formal religious organization. Originally, the Friends were the followers of George Fox, an English lay preacher who, about 1647, began to preach the doctrine of "Christ within"; this concept later developed as the idea of the "inner light." Although Fox did not intend to establish a separate religious body, his followers soon began to group together into the semblance of an organization, calling themselves by such names as Children of Light, Friends of Truth, and, eventually, Society of Friends. In reference to their agitated movements before moments of divine revelation, they were popularly called Quakers. The first complete exposition of the doctrine of "inner light" was written by the Scottish Quaker Robert Barclay in An Apology for the True Christian Divinity, as the Same Is Held Forth and Preached by the People Called in Scorn Quakers (1678), considered the greatest Quaker theological work.

The Friends were persecuted from the time of their inception as a group. They interpreted the words of Christ in the Scriptures literally, particularly, "Do not swear at all" (Matthew 5:34), and "Do not resist one who is evil" (Matthew 5:39). They refused, therefore, to take oaths; they preached against war, even to resist attack; and they often found it necessary to oppose the authority of church or state. Because they rejected any organized church, they would not pay tithes to the Church of England. Moreover, they met publicly for worship, a contravention of the Conventicle Act of 1664, which forbade meetings for worship other than that of the Church of England. Nevertheless, thousands of people, some on the continent of Europe and in America as well as in the British Isles, were attracted by teachings of the Friends.

Friends began to immigrate to the American colonies in the 1660s. They settled particularly in New Jersey, where they purchased land in 1674, and in the Pennsylvania colony, which was granted to William Penn in 1681. By 1684, approximately 7000 Friends had settled in Pennsylvania. By the early 18th century, Quaker meetings were being held in every colony except Connecticut and South Carolina. The Quakers were at first continuously persecuted, especially in Massachusetts, but not in Rhode Island, which had been founded in a spirit of religious toleration. Later, they became prominent in colonial life, particularly in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island. During the 18th century the American Friends were pioneers in social reform; they were friends of the Native Americans, and as early as 1688 some protested officially against slavery in the colonies. By 1787 no member of the society was a slave owner. Many of the Quakers who had immigrated to southern colonies joined the westward migrations into the Northwest Territory because they would not live in a slave-owning society.

John James was a Seventh Day Baptist Elder in London. He was tried and sentenced, executed, burned and quartered for allegedly preaching sedition by the Government. He was accused of being an alleged member of the Fifth Monarchy Men. There was little factual evidence to convict. He was martyred as an example for others. His head was placed on a pole/pike in Whitechapel (London) near his congregation.

There are indications of both Seventh Day General Baptists, and Seventh Day Particular Baptists congregations existing during this period. Seventh Day Baptist congregations survived the Restoration(1660), and many of these prospered in the New World.

All Baptist groups faced some form of persecution after the Restoration (1660) and were watched. Lingering Anabaptist connections persisted, and their earlier associations with former radical sects, and a few fire brands among the faithful added to their radical reputation to the Crown.

The English church at the time was Episcopalian and the Scottish settlers were Presbyterian. The Presbyterians believed in allegiance to God only and to God directly. Charles I, who was King from 1625-1649, persecuted these Presbyterians who maintained their independence and refused to convert to Episcopalianism. The native Irish who were Roman Catholic, also were opposed to these influx of "outsiders" and in 1641 they massacred many of these Scotch-Irish until Scotland ,who had maintained an interest in their sons and daughters who had moved west to Ireland, sent 10,000 troops to retake the area. Charles II, who was King from 1660-1685, continued the persecution of the Presbyterians. When the Roman Catholic James II, who succeeded his brother Charles II, was dethroned in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and succeeded by the protestant William of Orange the Presbyterian persecutions were no longer a problem. These Scotch Presbyterians endured many hardships and persecutions, but they held stubornly to their protestant ways and they never ceased to fight for their rights and their beliefs including the belief in a government by democracy as was the very structure of their church.

The religious persecution that drove settlers from Europe to the British North American colonies sprang from the conviction, held by Protestants and Catholics alike, that uniformity of religion must exist in any given society. This conviction rested on the belief that there was one true religion and that it was the duty of the civil authorities to impose it, forcibly if necessary, in the interest of saving the souls of all citizens. Nonconformists could expect no mercy and might be executed as heretics. The dominance of the concept, denounced by Roger Williams as "inforced uniformity of religion," meant majority religious groups who controlled political power punished dissenters in their midst. In some areas Catholics persecuted Protestants, in others Protestants persecuted Catholics, and in still others Catholics and Protestants persecuted wayward coreligionists. Although England renounced religious persecution in 1689, it persisted on the European continent. Religious persecution, as observers in every century have commented, is often bloody and implacable and is remembered and resented for generations.

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.tiz a fack that minny of them foundin fathers wuz christchun. tiz also a fack that minny of em wuz deists n most of em were influenced by the enlightenment.